In Ghana, “culture” is a term used to describe traditional drumming, dance and song performed by “culture groups”. Ghana Culture Groups were first formed during the steady urbanisation that occurred in Ghana during the second half of the 20th Century. Ghana had gained independence from the British in 1957 and, in the decades that followed, wished to re-embrace its culture and traditions.

As people from across of Ghana migrated from villages to towns and cities, such as Accra and Kumasi, in order to gain employment, many different tribal cultures were mixed together in one place.

Where previously the traditions of the Ga tribe had governed the culture of the Greater Accra region, the influx of migrants from other tribal regions, such as the Akan tribes from the west, the Ewes from the east and Dagomba tribes from the Islamic north, have made Accra into a multi-cultural melting pot.

With the mixing of tribes came the mixing of cultures, traditions and rituals. Music and dance, as an integral part of everyday tribal life, was seen as a way of preserving tribal identity. However, while individual tribal identity was seen as important (many Ghanaians still carry their tribal markings), the identity of “African” in the post-colonial era stirred just as much pride in the hearts of Ghanaians.

Although the sharing of folkloric culture was widely an organic process, there were individuals who had a major impact on spreading the music of Ghana’s tribes by formally studying and chronicling the music and dance traditions of different peoples.

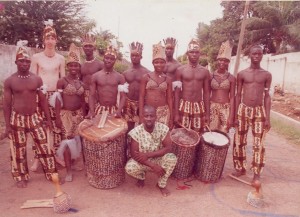

Mustapha Tettey Addy, a Ga drummer from the Greater Accra region, worked as a drummer and dancer at the University of Ghana in the 1960s. He met many specialist drummers from other regions of Ghana while at the university and began to build a comprehensive knowledge of folkloric music, dance and song. After leaving the University in 1965, he toured Ghana for several years collecting traditional songs and rhythms from tribes all over the country.

His great reputation as a virtuoso drummer and teacher also took him overseas to Europe and America. Following a period living in Germany, Addy moved back to Ghana and continued to study Ghanaian culture. In 1988 he set up the African Academy of Music and Arts (AAMA) in Kokrobite, west of Accra, where he has educated a generation of drummers, both local and tourist, since.

Repertoire performed in the culture groups of Greater Accra owe a lot to the research and teachings of Addy, who also added his own dance, Fume Fume, to the culture repertoire.

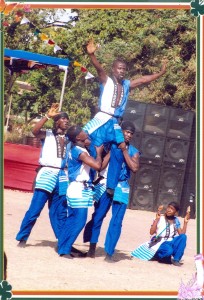

The culture groups of today perform the traditional drumming, dance and songs of many tribes from across Ghana, passed on by prominent master-drummers such as Addy and his nephews. Each tribal song sung has its language, with its own distinctive dancing style accompanied by its specific tribal dance rhythms and variations played on that unique set of tribal instruments.

Increasingly versatile, Ghanaian musicians of the present day now pick up traditional culture from further afield with the aid of CDs and videos from other West African countries. Djembefolas such as the famous Mamady Keita from Guinea are largely unwittingly responsible for popularising the djembe in Ghana, a drum used in almost every Ghanaian culture performance.

While traditional drumming or dancing connoisseurs of each style of music picked up by urban culture groups will see some dissipation in the nuances of their tribe’s music, the versatile performances of talented urban drummers and dancers can be breathtaking and impressively diverse.

In modern Ghana, music is divided into distinct genres including: traditional folk music (preserved true to its ritualistic heritage in the more remote villages); culture music (a hybrid of traditional and more modern folk music, performed mainly in urban areas); highlife (pop music of 1960s-1970s combining folk with modern electric instruments); gospel music (modern religious music, pop and often reggae influenced); hiplife (music of the current western-influenced generation, fusing hip hop with African pop music).

The one unifying aspect of all these musics is a strong dancing beat. Africa’s love of dance has been ingrained since pre-historic times – all African music, whether it be a modern pop hit or an ancient raindance, is guaranteed to fulfil the purpose of dance music. Perhaps one of the reasons why culture music is so important in Ghana’s developing cities is because it connects the young generation with their cultural identity. The traditional dances performed by culture groups are a form of story-telling, often documenting important historical events or recounting ancestral folk tales.

War-dances such as Achagbeko, an Ewe dance, or rain dances such as Bamaya, from northern Ghana, connect today’s youth with their rich tribal and national heritage.

Culture forms an intimate connection between all Ghanaians, from modern urban factory-workers in Accra to village-dwelling fishermen on the banks of Lake Volta. It is an expression of national pride, and bridges the growing gap not only between town and village life, but also between the young and old in Ghana – unifying them all under one beat.

Laurence Hill